The advantages of choosing Montenegro for political migration have already been described, but we consider that a more detailed explanation would be beneficial.

Before anything else, it should be made clear what the Montelibero project is NOT. Notably, it is not suitable for people considering emigration as a means to quickly improve their life or increase their income: Montenegro is not the most suitable place to obtain these short-term economic benefits.

It is always necessary to consider your goals and priorities. An aspiring entrepreneur hoping to become a billionaire and planning to raise venture capital for their innovative startup would find no better place for it than the Silicon Valley. A freelancer willing to live a luxurious life in a tropical paradise while earning a small remote income should direct their attention to Thailand, while Vietnam with its cheap labor would be more attractive for a business owner planning to mass-produce goods for the global market; whereas someone not limited by money and looking for the best quality of life might choose Switzerland or New Zealand. Finally, for those who do not care about the ever-expanding creep of authoritarianism and statism and are willing to trade liberty for security, there is little sense in migrating anywhere: as history has shown, conformists can adapt and even thrive under virtually any regime.

So, what IS Montelibero, after all? Simply put, it is a political migration project. We are not refugees fleeing their countries in search of better life; rather, we are fighters retreating to a strategically advantageous position, to regroup, reorganize and start the advance towards the long-needed reforms. We aim to advocate for the expansion of civil liberties, to promote free market economy and to drive the social and political innovation towards a radically new structure of society which is known as the “polystate”, “post-state” or “panarchy”.

We recognize that lowering the quality of the participants’ life is counterproductive to our goals: to be active and creative, everyone needs to be able to satisfy their basic needs, so solving the first-line economic tasks is currently our priority. It is evident that any attempts at political lobbying should come only after the foundations for a reasonably comfortable life have been laid.

Nevertheless, our project aims not only to relocate like-minded individuals and improve their life, but also to enable them to peacefully and lawfully promote and implement long-term solutions for improving the life of society in general: at least by developing and reaching prosperity together with the new home country; at best, by starting the “domino effect” by encouraging like-minded individuals from other countries to follow our example. A successful implementation of our ideas in a country open to change and innovation would serve as a proof-of-concept, helping the ideas spread and gain more support, motivating people all over the world to break free of the chains of authoritarianism.

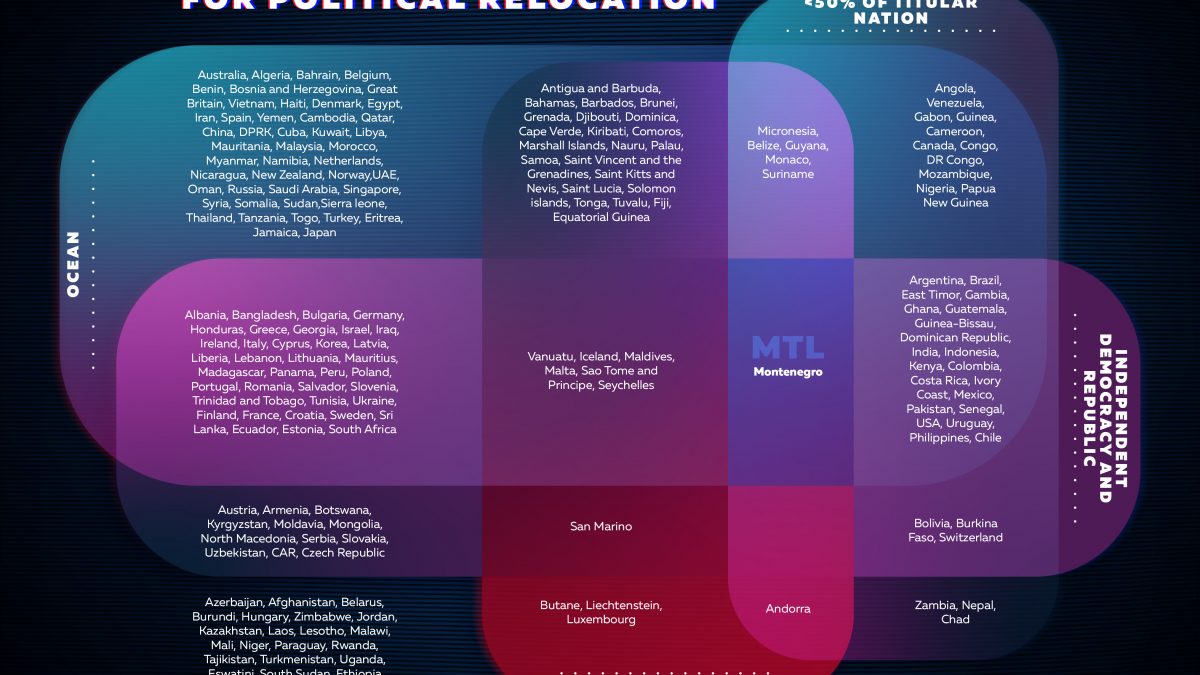

Let’s consider the conditions the country should ideally meet to be suitable for the project goals: both primary (keeping the acceptable quality of life and improving it over time) and secondary (driving the aforementioned social and political changes).

The country must be sovereign and have a peaceful democratic regime. It is easy to see that a country ruled by a single party (even masquerading its regime as a democracy) or a dictator, occupied by another state or torn apart by a civil war is not the place for a group of immigrants to advocate for political reform without running the risk of serious harm or death.

The country must be sovereign and have a peaceful democratic regime. It is easy to see that a country ruled by a single party (even masquerading its regime as a democracy) or a dictator, occupied by another state or torn apart by a civil war is not the place for a group of immigrants to advocate for political reform without running the risk of serious harm or death.

The suitability of constitutional monarchies, including those under the reign of Queen Elizabeth the Second, is also questionable. Many of those are small island states, quite appealing in all of the other aspects; nevertheless, we assume that people who have not yet sought to replace monarchy with republicanism would possibly not be interested in the ideas of post-state or panarchy. We do acknowledge that the innate conservatism of these constitutional monarchies, notably the Commonwealth ones, safeguards their societies from going down the path of populism, tribalism or straight-up dictatorship, but it also impedes social and political innovation and perpetuates the sacralization of state power, which many advocates of spontaneous order consider to be the root cause of many modern social, political and economic issues.

- Another important condition is the lack of an ethnic majority. The reasons for that are similar: a nation state may be essential to keep its democratic regime stable, but it puts political migrants into a disadvantageous

position: being part of both an outgroup and an ethnic minority lessens the likelihood of their voices being heard and their opinions considered. The lack of such a majority, on the other hand, increases the chances of a new ethnocultural group to successfully integrate into society and start influencing it.

position: being part of both an outgroup and an ethnic minority lessens the likelihood of their voices being heard and their opinions considered. The lack of such a majority, on the other hand, increases the chances of a new ethnocultural group to successfully integrate into society and start influencing it.

A more fundamental (but not immediately obvious) point against choosing countries with an ethnic majority is as follows. In a situation where multiple culturally opposing groups exist in a country, people tend to support members of their ethnocultural in-group both in daily life and when making political decisions (such as when voting at elections). If such groups are approximately equal in manpower and political representation, the stakes are massively raised during each election over the risk of losing to an outgroup. This stresses the political system, sometimes to a breaking point, but we theorize that this stress could be taken advantage of: if it does not result in societal collapse and civil war (see condition 1), it could be used as a catalyst to boost the transition into a panarchic post-state society, because people may see a decentralized and demonopolized system as a lesser evil compared to a government run by members of their outgroup. We recognize that successfully avoiding both a political stagnation with the government catering to the majority’s needs and a war between opposing ethnocultural groups is an extremely difficult task for a given country’s society, but we see it as a necessity to reach a new stage of political development. The difficulty of this transition could explain why no such processes have ever been observed compared to much more destructive, but obvious solutions like assimilation of the minority or dissolution of the country.

- Access to the ocean is another aspect we consider crucial for the country of choice, for reasons given below.

— Ocean access permits integration into the global trade, which greatly aids in raising the standards of living for all members of society and in attracting entrepreneurs and investors, driving the creation of jobs. Other ways also exist, like the one Switzerland went by developing their banking industry, but they are much more time-consuming and labor-intensive.

— Ocean access permits integration into the global trade, which greatly aids in raising the standards of living for all members of society and in attracting entrepreneurs and investors, driving the creation of jobs. Other ways also exist, like the one Switzerland went by developing their banking industry, but they are much more time-consuming and labor-intensive.

— Another important but lesser known advantage of having ocean access lies in the opportunities offered by yachting. Owning private vessels for traveling and even semi-permanent or permanent living could in many cases be cheaper than owning real estate on land, while giving the owner an uncontested level of independence and freedom. We believe that someday living on a personal seafaring vessel will become as widespread among libertarians as using cryptocurrencies for payments and small arms for self-defence. More information on this could be found here.

Obtaining access to the ocean would allow us not only to create comfortable environment for the development of personal yachting, but also to attract existing like-minded yacht owners to our project. Furthermore, this also allows for a “Plan B” of sorts – even if the land-based project were to fail, the existing fleet and necessary infrastructure would allow us to consider a more radical seasteading — based approach to political migration.

- Finally, the country of our choice should have a small enough population, so that every individual citizen would have a greater chance to influence the society in general. That would make supporting like-minded people and winning over opponents much easier: all other things equal, convincing ten people is faster and cheaper than a thousand.

It is also worth noting that politics and society are chiefly influenced not by a simple numerical majority but rather by the most vocal and active minorities. By a conservative estimation, the threshold at which an active like-minded minority becomes significant is somewhere around 3.5% of the general populace. This stands true for any given society, but, as shown above, smaller populations require less people and resources to influence.

We decided to set the cutoff for the population factor at 1 million people. While somewhat arbitrary, this number still leaves enough countries to choose from while being low enough for us to potentially reach the aforementioned 3.5% threshold in our lifetimes.

It is worth noting that the country should meet all four of the aforementioned criteria to be considered suitable for our project. E.g. a country small enough population-wise, but ruled by a dictator or having an ethnic majority would likely not accept foreigners, especially those with novel sociopolitical ideas.

Keeping in mind the long-term nature of our project and its global goals, we decided to discard the factors usually considered by people who migrate to obtain short-term economic benefits, like the racial, cultural and geographical factors, human development index and GDP per capita. We also rejected the idea of considering the political ideology of the target country’s population and ruling parties, even though a sizable majority of the countries in question have sufficiently inhospitable authoritarian and/or anti-capitalist regimes. This increases our risks of being forced to choose a remote and poor third world country, with a culture vastly different from ours, but intellectual and methodological honesty obliges us to take these risks. And, after finishing our research, we have to admit that we were lucky to stop on the very decent option of choosing Montenegro.

We should briefly stop on each of the few other countries with similar characteristics according to our criteria.

Countries with questionable sovereignty, i.e. those still under monarchy rule (even the most constitutional and democratically-inclined ones) require the added spending of time and resources to first shift the cultural paradigm away from the idea of worshipping state power embodied in their ruling dynasties before making a vastly more radical step towards a panarchic post-state. These actions would also very likely run contrary to the interests of the ruling house and its associated structures, so to avoid being compromised (or straight up eliminated) by MI6 or some other agency we chose to reject Belize and Monaco. The situation with Pacific microstates is very similar, many of them associated with the Commonwealth or the United States. Given the decided asymmetry of these relationships (in contrast to the relative equality of the EU membership, which is expected for Montenegro) and especially the microstates’ dependence on their major partners for defence and financial aid, these countries have been also deemed unsuitable due to high risks of running afoul of MI6 or the Pentagon, with understandable results.

We also considered Uruguay, Timor-Leste and Guinea-Bissau, but, while quite appealing in other aspects, these countries have an unacceptably large population.

Surinam’s regime remains unstable, with a nonzero probability of military coups and civil war, which makes it unsuitable for us due to the lack of a peaceful democratic rule.

Guyana had mostly been ruled by left-wing parties for the last 60 years, since the gaining of independence. Ironically, if we were to make our research before the August of 2020, Montenegro would have been in a similar position (though much more pro-free market and with a weaker ruling coalition), but since then the ruling party (successor and heir of the Communist one) had lost its grip on power, providing the long-needed opportunities for political competition and discussion. Time will tell if something similar would happen in Guyana.

Finally, we had to reject the (otherwise) wonderful islands of the Seychelles due to them having a well-defined ethnic majority of Seychellois Creoles.

This sums up all of the borderline and questionable cases. The full analysis of all 194 countries (up-to-date for the spring of 2021) could be found here. As usual, we welcome any feedback, and invite those interested in discussing the topic to our chat.

To be honest with ourselves and our readers, we have to admit that we have already unconsciously singled out Montenegro and feared that it would not pass our selection criteria, which could have resulted in additional arguments regarding logistics and ease of travel. This would have invalidated our methodology and make the end result more subjective, but our fears were unfounded, as our search failed to net us viable alternatives to Montenegro. Nevertheless, should you feel the need to join the discussion, we welcome you to our chat.

1 Комментарий

English speaker